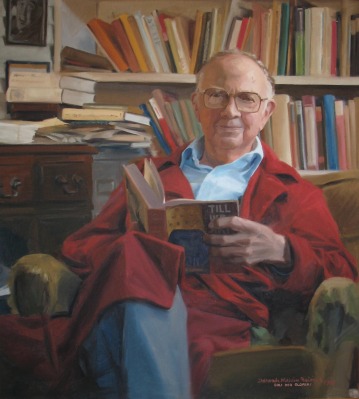

September “Artifact of the Month” – Portrait of Clyde S. Kilby by Deborah Melvin Beisner, 1987. Oil on canvas with the inscription “Soli Deo Gloria.”

The September Artifact of the Month is an oil portrait of Wade Center founder Dr. Clyde S. Kilby, painted by Deborah Melvin Beisner in 1987, and given to the Wade by Leanne Payne in 2011. This month’s artifact not only highlights an interesting piece of memorabilia archived at the Wade Center; it also celebrates the legacy of the founder and first director of the Marion E. Wade Center, Dr. Clyde S. Kilby.

Born on September 26, 1902, Dr. Kilby taught English literature at Wheaton College from 1935 until 1981. During that time he was deeply affected by the writings of C.S. Lewis and began a correspondence with him. After Lewis’s death in 1963, Dr. Kilby began to gather together books and papers related not only to C.S. Lewis, but also to six other British authors who were connected to Lewis in terms of literary and spiritual thought. From this modest beginning has grown the internationally recognized research collection now known as the Marion E. Wade Center.

Dr. Kilby was a well-loved professor at Wheaton, and many students were shaped and inspired by his teaching and his personal mentorship. He and his wife, Martha, regularly welcomed students into their home for meals and conversation, introducing them to their talking pet parakeet and discussing faith, literature, and the imagination, as well as any issues or questions a given student might have. One such student who benefited from the Kilbys’ friendship was Marilee Melvin, now the executive assistant to Wheaton College President Philip G. Ryken and a Wade Center Board member.

Marilee’s mother remembered Dr. Kilby as one of her favorite professors at Wheaton, and during her own time as a student at Wheaton (from 1968-1972), Marilee took Dr. Kilby’s courses on Romantic literature and “Modern Mythology,” getting to know him better and finding her own life and faith enriched by the literature he loved and taught.

“Students tend to love what their professors and mentors love,” explains Marilee. “But in the case of Dr. Kilby’s vision for the Wade authors . . . he was at the cutting edge of studying these authors, and in turn, introducing others to a body of literature intrinsically important for spiritual formation as well as intellectual stimulation.”

As a senior, Marilee began visiting with the Kilbys at their home, and a friendship developed, only growing stronger after she graduated. During that time, Dr. Kilby continued to send her encouraging letters throughout her studies as a graduate student at the University of Chicago, and later when she worked in various areas of the United States government in Washington, DC. Today Marilee remembers Dr. Kilby for some of his most characteristic traits and qualities: “His love of the subject matter, which in turn ignited an interest in and love of the material in his students; his cheerful, even cherubic countenance, and joyful heart, that spilled over in positive encouragement; his love of the particular, the real, which revealed his capacity for wisdom as well as his scholarship; and his stopping, literally and figuratively, to smell the roses.”

Marilee was Wheaton College’s vice president for alumni relations for nearly 18 years, and during her time in that position, she “heard many stories from alumni who, as students in trouble of some kind or another, found in Dr. Kilby’s wise and gracious response and help just what they needed.” “Wise and gracious” also characterized the welcome Dr. Kilby gave to students, visitors, and scholars to the Wade Center during his time as its director, and the words still describe the quality of attention and personal investment given to those who enter the Wade’s doors today.

Marilee’s friendship with the Kilbys, and her excitement over Dr. Kilby’s founding of what was originally called “The C.S. Lewis Collection,” helped introduce all eight of her siblings to Lewis’s world of Narnia. Marilee’s younger sister, Deborah Melvin Beisner, grew to know the Kilbys through becoming acquainted with them around her parents’ dining room table as the two families spent time together.

After graduating from Hillsdale College in Michigan, Deborah worked in the Wheaton area. She lived a few blocks from the Kilbys and regularly visited with them. She says, “I was fond of walking over to sit amongst his prized day lily collection, imagining eldil, or sharing a meal with Peter Kilby—the parakeet— sitting on the doctor’s thin hair, or listening to him talk in his upstairs back porch library/study. Oh, the magic!”

A visual artist who studied closely with the portrait painter John Howard Sanden, Deborah desired to paint Dr. Kilby and had a photography session with him seated in his porch library in a familiar housecoat, reading his favorite work by C.S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces.

“When I had chosen the final composition from the photographs taken that day, I stretched a canvas and penciled in the outlines,” she explains. “However, my painting career got interrupted with a little thing called marriage, and the unpainted canvas followed us around until my second child was born in September 1986. My baby daughter received a letter from Dr. Kilby . . . welcoming her to the world—the world he left just days later. Now I really wanted to finish the portrait. Our mutual friend, Leanne Payne, agreed to commission its completion, and my husband took time to watch our children while I painted in our laundry room.”

The completed portrait was graciously donated to the Wade Center by Leanne Payne, the founder and president of Pastoral Care Ministries (now Ministries of Pastoral Care). Today its colors shine brightly from the wall of the Wade’s upstairs seminar room, where Dr. Kilby’s own library and some of his personal memorabilia are displayed—an inviting space where gatherings take place under the kindly smile of Dr. Kilby, and where the “conversation” he began nearly half a century ago continues.

Deborah Melvin Beisner lives in Pembroke Pines, Florida, with her scholar/writer husband, E. Calvin Beisner, and is back at the easel now that her kids have grown. She and her husband have seven children and five grandchildren. You can see more of her paintings at http://debbeisner.wix.com/deborahmelvinbeisner.

Learn more about the life and legacy of Clyde S. Kilby on the Wade Center’s website.